Radiative Equilibrium

Contents

Radiative Equilibrium#

This notebook is a slightly modified chapter of the excellent The Climate Laboratory by Brian E. J. Rose, University at Albany.

NOTE: from v0.8 of climlab the fortran extensions need to be compiled separately. I found the best way to do this was to switch to using a conda environment, which I did by using mamba, which is much faster.

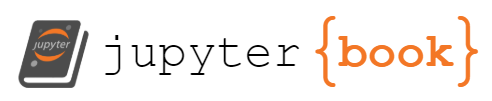

1. The observed annual, global mean temperature profile#

Let’s look at the observations of air temperature from the NCEP Reanalysis data.

In this notebook we’ll define a function to create the Skew-T diagram, because later we are going to reuse it several times.

Click to expand code cells to see Python details

# This code is used just to create the skew-T plot of global, annual mean air temperature

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import xarray as xr

from metpy.plots import SkewT

# tompkins additional packages

from cdo import Cdo

import cdsapi

from netCDF4 import Dataset

ncep_url = "http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/thredds/dodsC/Datasets/ncep.reanalysis.derived/"

ncep_air = xr.open_dataset( ncep_url + "pressure/air.mon.1981-2010.ltm.nc", use_cftime=True)

# Take global, annual average

coslat = np.cos(np.deg2rad(ncep_air.lat))

weight = coslat / coslat.mean(dim='lat')

Tglobal = (ncep_air.air * weight).mean(dim=('lat','lon','time'))

def make_skewT():

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

skew = SkewT(fig, rotation=30)

skew.plot(Tglobal.level, Tglobal, color='black', linestyle='-', linewidth=2, label='Observations')

skew.ax.set_ylim(1050, 10)

skew.ax.set_xlim(-90, 45)

# Add the relevant special lines

skew.plot_dry_adiabats(linewidth=0.5)

skew.plot_moist_adiabats(linewidth=0.5)

#skew.plot_mixing_lines()

skew.ax.legend()

skew.ax.set_xlabel('Temperature (degC)', fontsize=14)

skew.ax.set_ylabel('Pressure (hPa)', fontsize=14)

return skew

skew = make_skewT()

Here we are going to work with some detailed Single-Column Models to understand questions such as

What physical factors actually determine this profile?

Would the profile be different with different gases in the atmosphere?

What are the relative roles of radiation and dynamics (i.e. motion!) in setting this profile?

We will start by ignoring all processes except radiation. We will calculate something called the radiative equilibrium temperature.

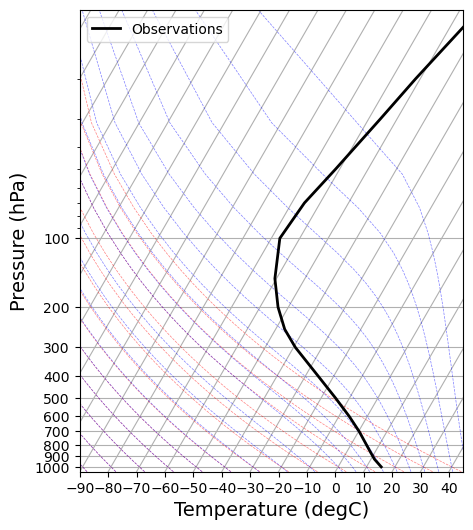

2. Radiative equilibrium – the concept#

Models of radiative transfer slice up the atmospheric air column into a series of layer, and calculate the emission and absorption of radiation within each layer.

It’s really just a generalization of the model we already looked at:

The concept of radiative equilibrium means that we ignore all methods of heat exchange except for radiation, and ask what temperature profile would exist under that assumption?

We can answer that question by using a radiative transfer model to explicity compute the shortwave and longwave beams, and the warming/cooling of each layer associated with the radiative sources and sinks of energy.

Basically, we reach radiative equilibrium when energy is received and lost through radiation at the same rate in every layer.

Because of the complicated dependence of emission/absorption features on the wavelength of radiation and the different gases, the beam is divided up into many different pieces representing different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.

We will not look explicitly at this complexity here, but we will use a model that represents these processes at the same level of detail we would in a GCM.

3. Setting up a single-column radiation model in climlab#

Radiation models in climlab#

We’re now going to use climlab to run a complex radiation model, one that accounts for the spectral absorption properties of different gases.

climlab actually provides two different “GCM-level” radiation codes:

The CAM3 radiation module from NCAR (essentially the same radiation code used in our CESM simulations)

The RRTMG (Rapid Radiative Transfer Model) which is used in many current GCMs.

The links above take you to the online climlab documentation.

We’re going to use a model called the Rapid Radiative Transfer Model or RRTMG. This is a “serious” and widely-used radiation model, used in many comprehensive GCMs and Numerical Weather Prediction models.

climlab provides an easy-to-use Python wrapper for the RRTMG code.

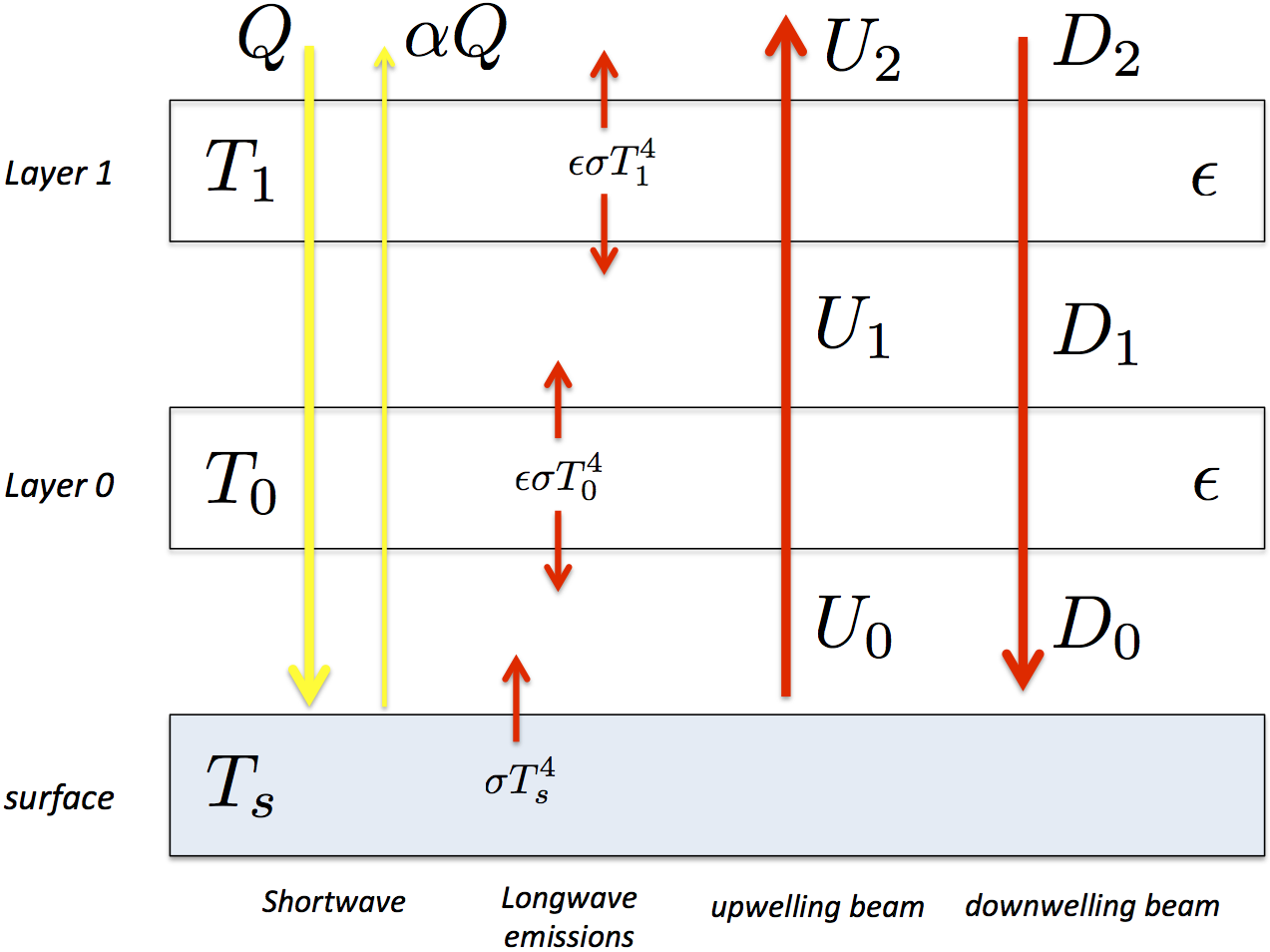

Water vapor data#

Before setting up the model, we need some water vapor data. Why? Because our model needs to know how much water vapor exists at each vertical level, since water vapor is a radiatively important gas.

We’re going to use the specific humidity from the ERA5 reanalysis, we will just take a single monthly average as a starting point. First We’ll just take the global, time average of this data, and plot its vertical profile.

first the retrieval:

# Take a look at what we just calculated ... it should be one-dimensional (vertical levels)

c = cdsapi.Client()

qvfile="./qv.nc"

# set to true to get data

if True:

res=c.retrieve(

'reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels-monthly-means',

{

'format': 'netcdf',

'product_type': 'monthly_averaged_reanalysis',

'variable': 'specific_humidity',

'pressure_level': [

'1', '2', '3',

'5', '7', '10',

'20', '30', '50',

'70', '100', '125',

'150', '175', '200',

'225', '250', '300',

'350', '400', '450',

'500', '550', '600',

'650', '700', '750',

'775', '800', '825',

'850', '875', '900',

'925', '950', '975',

'1000',

],

'year': '2020',

'month': '09',

'time': '00:00',

},

qvfile)

2023-03-30 12:06:27,181 INFO Welcome to the CDS

2023-03-30 12:06:27,182 INFO Sending request to https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/api/v2/resources/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels-monthly-means

2023-03-30 12:06:27,300 INFO Request is completed

2023-03-30 12:06:27,301 INFO Downloading https://download-0020.copernicus-climate.eu/cache-compute-0020/cache/data6/adaptor.mars.internal-1680121731.3435478-31690-6-ad214745-7e44-43dd-ad57-0ec733208b37.nc to ./qv.nc (73.3M)

2023-03-30 12:07:34,386 INFO Download rate 1.1M/s

Now take the global, annual average of the specific humidity:

# if you prefer to average within python you need to use cos(lat) weighting don't forget

cdo = Cdo()

Qglobal2=cdo.fldmean(input="qv.nc")

qvfile=Dataset(Qglobal2)

Qglobal=qvfile.variables["q"][:].flatten()

Qglobal.lev=qvfile.variables["level"][:]

print (Qglobal.lev)

[ 1 2 3 5 7 10 20 30 50 70 100 125 150 175

200 225 250 300 350 400 450 500 550 600 650 700 750 775

800 825 850 875 900 925 950 975 1000]

And make a figure:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

# Multiply Qglobal by 1000 to put in units of grams water vapor per kg of air

ax.plot(Qglobal, Qglobal.lev)

ax.invert_yaxis()

ax.set_ylabel('Pressure (hPa)')

ax.set_xlabel('Specific humidity (kg/kg)')

ax.grid()

This shows a typical climatological humidity profile. Water vapor is a trace gas! But as we will see, it plays a very important role.

Based on this figure, where is most of the water vapor?

Create a single-column model on the same grid as this water vapor data:#

Here we will create the grid and state variables (air and surface temperature) for our single-column model.

import climlab

# Make a model on same vertical domain as the GCM

mystate = climlab.column_state(lev=Qglobal.lev, water_depth=2.5)

print(mystate)

AttrDict({'Ts': Field([288.]), 'Tatm': Field([200. , 202.16666667, 204.33333333, 206.5 ,

208.66666667, 210.83333333, 213. , 215.16666667,

217.33333333, 219.5 , 221.66666667, 223.83333333,

226. , 228.16666667, 230.33333333, 232.5 ,

234.66666667, 236.83333333, 239. , 241.16666667,

243.33333333, 245.5 , 247.66666667, 249.83333333,

252. , 254.16666667, 256.33333333, 258.5 ,

260.66666667, 262.83333333, 265. , 267.16666667,

269.33333333, 271.5 , 273.66666667, 275.83333333,

278. ])})

radmodel = climlab.radiation.RRTMG(name='Radiation (all gases)', # give our model a name!

state=mystate, # give our model an initial condition!

specific_humidity=Qglobal, # tell the model how much water vapor there is

albedo = 0.25, # this the SURFACE shortwave albedo

timestep = climlab.constants.seconds_per_day, # set the timestep to one day (measured in seconds)

)

print(radmodel)

climlab Process of type <class 'climlab.radiation.rrtm.rrtmg.RRTMG'>.

State variables and domain shapes:

Ts: (1,)

Tatm: (37,)

The subprocess tree:

Radiation (all gases): <class 'climlab.radiation.rrtm.rrtmg.RRTMG'>

SW: <class 'climlab.radiation.rrtm.rrtmg_sw.RRTMG_SW'>

LW: <class 'climlab.radiation.rrtm.rrtmg_lw.RRTMG_LW'>

Explore the single-column model object#

Look at a few interesting properties of the model we just created:

# Here's the state dictionary we already created:

radmodel.state

AttrDict({'Ts': Field([288.]), 'Tatm': Field([200. , 202.16666667, 204.33333333, 206.5 ,

208.66666667, 210.83333333, 213. , 215.16666667,

217.33333333, 219.5 , 221.66666667, 223.83333333,

226. , 228.16666667, 230.33333333, 232.5 ,

234.66666667, 236.83333333, 239. , 241.16666667,

243.33333333, 245.5 , 247.66666667, 249.83333333,

252. , 254.16666667, 256.33333333, 258.5 ,

260.66666667, 262.83333333, 265. , 267.16666667,

269.33333333, 271.5 , 273.66666667, 275.83333333,

278. ])})

# Here are the pressure levels in hPa

radmodel.lev

array([ 1., 2., 3., 5., 7., 10., 20., 30., 50.,

70., 100., 125., 150., 175., 200., 225., 250., 300.,

350., 400., 450., 500., 550., 600., 650., 700., 750.,

775., 800., 825., 850., 875., 900., 925., 950., 975.,

1000.])

There is a dictionary called absorber_vmr that holds the volume mixing ratio of all the radiatively active gases in the column:

radmodel.absorber_vmr

{'CO2': 0.000348,

'CH4': 1.65e-06,

'N2O': 3.06e-07,

'O2': 0.21,

'CFC11': 0.0,

'CFC12': 0.0,

'CFC22': 0.0,

'CCL4': 0.0,

'O3': array([3.32452359e-06, 5.49765445e-06, 7.03108249e-06, 8.17280656e-06,

8.49624970e-06, 8.49933725e-06, 6.47842360e-06, 4.48576690e-06,

2.25137178e-06, 1.13532298e-06, 5.32009049e-07, 3.46334801e-07,

2.45552383e-07, 1.90806332e-07, 1.51755709e-07, 1.19700066e-07,

9.29020109e-08, 6.59109748e-08, 5.57122567e-08, 5.02096369e-08,

4.60528063e-08, 4.29407799e-08, 4.08899052e-08, 3.91554265e-08,

3.76122833e-08, 3.54532697e-08, 3.31238355e-08, 3.18505117e-08,

3.05754534e-08, 2.93003951e-08, 2.80298557e-08, 2.69906527e-08,

2.59514497e-08, 2.49122466e-08, 2.38730436e-08, 2.28798533e-08,

2.19124599e-08])}

Most are just a single number because they are assumed to be well mixed in the atmosphere.

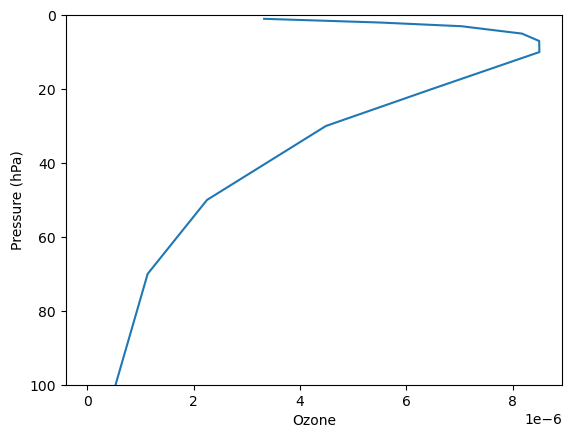

The exception is ozone, which has a vertical structure taken from observations. Let’s plot it

# E.g. the CO2 content (a well-mixed gas) in parts per million

radmodel.absorber_vmr['CO2'] * 1E6

348.0

Python exercise: plot the ozone profile#

Make a simple plot showing the vertical structure of ozone, similar to the specific humidity plot we just made above.

# here is the data you need for the plot, as a plain numpy arrays:

print(radmodel.lev)

print(radmodel.absorber_vmr['O3'])

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

# Multiply Qglobal by 1000 to put in units of grams water vapor per kg of air

ax.plot(radmodel.absorber_vmr['O3'], Qglobal.lev)

ax.invert_yaxis()

ax.set_ylim([100,0])

ax.set_ylabel('Pressure (hPa)')

ax.set_xlabel('Ozone')

[ 1. 2. 3. 5. 7. 10. 20. 30. 50. 70. 100. 125.

150. 175. 200. 225. 250. 300. 350. 400. 450. 500. 550. 600.

650. 700. 750. 775. 800. 825. 850. 875. 900. 925. 950. 975.

1000.]

[3.32452359e-06 5.49765445e-06 7.03108249e-06 8.17280656e-06

8.49624970e-06 8.49933725e-06 6.47842360e-06 4.48576690e-06

2.25137178e-06 1.13532298e-06 5.32009049e-07 3.46334801e-07

2.45552383e-07 1.90806332e-07 1.51755709e-07 1.19700066e-07

9.29020109e-08 6.59109748e-08 5.57122567e-08 5.02096369e-08

4.60528063e-08 4.29407799e-08 4.08899052e-08 3.91554265e-08

3.76122833e-08 3.54532697e-08 3.31238355e-08 3.18505117e-08

3.05754534e-08 2.93003951e-08 2.80298557e-08 2.69906527e-08

2.59514497e-08 2.49122466e-08 2.38730436e-08 2.28798533e-08

2.19124599e-08]

Text(0.5, 0, 'Ozone')

The other radiatively important gas is of course water vapor, which is stored separately in the specific_humidity attribute:

# specific humidity in kg/kg, on the same pressure axis

print(radmodel.specific_humidity)

[3.89581964e-06 3.54524763e-06 3.54524763e-06 3.19467562e-06

3.19467562e-06 3.19467562e-06 2.84410362e-06 2.84410362e-06

2.84410362e-06 2.84410362e-06 3.19467562e-06 4.24639165e-06

7.40153972e-06 1.47635519e-05 2.87864322e-05 5.15736127e-05

8.41768095e-05 1.82336972e-04 3.34835795e-04 5.48334148e-04

8.32297475e-04 1.20530609e-03 1.66420485e-03 2.16517225e-03

2.73274833e-03 3.40374315e-03 4.19708761e-03 4.65107836e-03

5.14468375e-03 5.70349553e-03 6.35135260e-03 7.02690486e-03

7.67826765e-03 8.34470503e-03 9.04199276e-03 9.51912126e-03

9.76417109e-03]

The RRTMG radiation model has lots of different input parameters#

For details you can look at the documentation

for item in radmodel.input:

print(item)

specific_humidity

absorber_vmr

cldfrac

clwp

ciwp

r_liq

r_ice

emissivity

S0

insolation

coszen

eccentricity_factor

aldif

aldir

asdif

asdir

icld

irng

idrv

permuteseed_sw

permuteseed_lw

dyofyr

inflgsw

inflglw

iceflgsw

iceflglw

liqflgsw

liqflglw

tauc_sw

tauc_lw

ssac_sw

asmc_sw

fsfc_sw

tauaer_sw

ssaaer_sw

asmaer_sw

ecaer_sw

tauaer_lw

isolvar

indsolvar

bndsolvar

solcycfrac

Many of the parameters control the radiative effects of clouds.

But here we should note that the model is initialized with no clouds at all:

# This is the fractional area covered by clouds in our column:

radmodel.cldfrac

0.0

4. Radiative equilibrium in the single-column model#

Step the model forward in time!#

Here are the current temperatures (initial condition):

radmodel.Ts

Field([288.])

radmodel.Tatm

Field([200. , 202.16666667, 204.33333333, 206.5 ,

208.66666667, 210.83333333, 213. , 215.16666667,

217.33333333, 219.5 , 221.66666667, 223.83333333,

226. , 228.16666667, 230.33333333, 232.5 ,

234.66666667, 236.83333333, 239. , 241.16666667,

243.33333333, 245.5 , 247.66666667, 249.83333333,

252. , 254.16666667, 256.33333333, 258.5 ,

260.66666667, 262.83333333, 265. , 267.16666667,

269.33333333, 271.5 , 273.66666667, 275.83333333,

278. ])

Now let’s take a single timestep:

radmodel.step_forward()

radmodel.Ts

Field([288.55188808])

The surface got warmer!

Let’s take a look at all the diagnostic information that was generated during that timestep:

Diagnostic variables in our single-column model#

Every climlab model has a diagnostics dictionary. Here we are going to check it out as an xarray dataset:

climlab.to_xarray(radmodel.diagnostics)

<xarray.Dataset>

Dimensions: (depth: 1, depth_bounds: 2, lev: 37, lev_bounds: 38)

Coordinates:

* depth (depth) float64 1.25

* depth_bounds (depth_bounds) float64 0.0 2.5

* lev (lev) float64 1.0 2.0 3.0 5.0 ... 925.0 950.0 975.0 1e+03

* lev_bounds (lev_bounds) float64 0.0 1.5 2.5 4.0 ... 962.5 987.5 1e+03

Data variables: (12/26)

OLR (depth) float64 233.2

OLRclr (depth) float64 233.2

OLRcld (depth) float64 0.0

TdotLW (lev) float64 -1.959 -1.48 -1.387 ... -0.004817 3.397

TdotLW_clr (lev) float64 -1.959 -1.48 -1.387 ... -0.004817 3.397

LW_sfc (depth) float64 96.79

... ...

SW_flux_up (lev_bounds) float64 86.48 86.4 86.36 ... 54.73 54.52

SW_flux_down (lev_bounds) float64 341.3 338.6 337.6 ... 219.4 218.1

SW_flux_net (lev_bounds) float64 254.8 252.2 251.3 ... 164.6 163.6

SW_flux_up_clr (lev_bounds) float64 86.48 86.4 86.36 ... 54.73 54.52

SW_flux_down_clr (lev_bounds) float64 341.3 338.6 337.6 ... 219.4 218.1

SW_flux_net_clr (lev_bounds) float64 254.8 252.2 251.3 ... 164.6 163.6The main “job” of a radiative transfer model it to calculate the shortwave and longwave fluxes up and down between each model layer.

For example:

climlab.to_xarray(radmodel.LW_flux_up)

<xarray.DataArray (lev_bounds: 38)>

array([233.22479476, 233.26435499, 233.31087491, 233.38959653,

233.5157132 , 233.67796863, 234.09866282, 234.85841428,

236.00225931, 237.37227575, 238.8283948 , 240.26482819,

241.53933487, 242.81179119, 244.1186905 , 245.49693462,

246.88714231, 248.68602032, 251.19168186, 254.0394867 ,

257.24849435, 260.828565 , 264.82727646, 269.31793278,

274.33026093, 279.98523551, 286.68643132, 293.67399561,

299.63961438, 305.87258623, 312.39839729, 319.27515233,

326.52905011, 334.17665787, 342.30875478, 351.31763881,

363.30681331, 390.099014 ])

Coordinates:

* lev_bounds (lev_bounds) float64 0.0 1.5 2.5 4.0 ... 937.5 962.5 987.5 1e+03These are upward longwave fluxes in W/m2.

Why are there 38 data points, when the model has 37 pressure levels?

radmodel.lev

array([ 1., 2., 3., 5., 7., 10., 20., 30., 50.,

70., 100., 125., 150., 175., 200., 225., 250., 300.,

350., 400., 450., 500., 550., 600., 650., 700., 750.,

775., 800., 825., 850., 875., 900., 925., 950., 975.,

1000.])

radmodel.lev_bounds

array([ 0. , 1.5, 2.5, 4. , 6. , 8.5, 15. , 25. ,

40. , 60. , 85. , 112.5, 137.5, 162.5, 187.5, 212.5,

237.5, 275. , 325. , 375. , 425. , 475. , 525. , 575. ,

625. , 675. , 725. , 762.5, 787.5, 812.5, 837.5, 862.5,

887.5, 912.5, 937.5, 962.5, 987.5, 1000. ])

The last element of the flux array represents the upward flux from the surface to the first level:

radmodel.LW_flux_up[-1]

390.0990139997316

The value is about 390 W m\(^{-2}\).

Why?

sigma = 5.67E-8

sigma * 288**4

390.0793946112

The surface temperature was initialized at 288 K, and the surface is treated as very close to a blackbody in the model.

What about the flux from the top layer out to space?

Two ways to access this information:

radmodel.LW_flux_up[0]

233.2247947597788

radmodel.OLR

Field([233.22479476])

Of course there is a whole other set of fluxes for the shortwave radiation.

One diagnostic we will often want to look at is the net energy budget at the top of the atmosphere:

radmodel.ASR - radmodel.OLR

Field([21.5964849])

Is the model gaining or losing energy?

Integrate out to equilibrium#

Here I want to step forward in time until the model is very close to energy balance.

We can use a while loop, conditional on the top-of-atmosphere imbalance:

while np.abs(radmodel.ASR - radmodel.OLR) > 0.01:

radmodel.step_forward()

Check the energy budget again:

# Check the energy budget again

radmodel.ASR - radmodel.OLR

Field([0.00991957])

Indeed, the imbalance is now small.

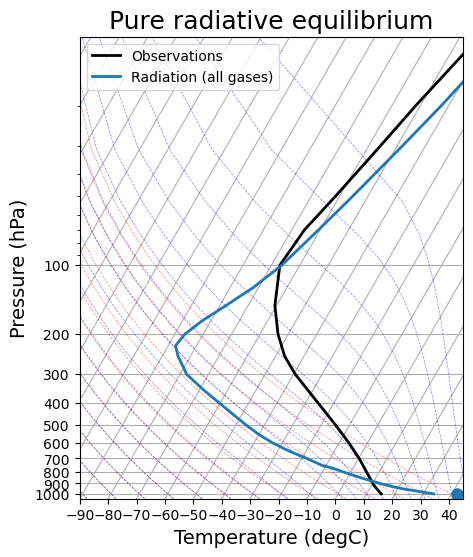

Compare the radiative equilibrium temperature to observations#

Here’s a helper function we’ll use to add model temperature profiles to our skew-T plot:

def add_profile(skew, model, linestyle='-', color=None):

line = skew.plot(model.lev, model.Tatm - climlab.constants.tempCtoK,

label=model.name, linewidth=2)[0]

skew.plot(1000, model.Ts - climlab.constants.tempCtoK, 'o',

markersize=8, color=line.get_color())

skew.ax.legend()

skew = make_skewT()

add_profile(skew, radmodel)

skew.ax.set_title('Pure radiative equilibrium', fontsize=18);

Tglobal

<xarray.DataArray (level: 17)>

array([ 15.179084 , 11.207003 , 7.8383274 , 0.21994135,

-6.4483433 , -14.888848 , -25.570469 , -39.36969 ,

-46.797905 , -53.652245 , -60.56356 , -67.006065 ,

-65.53293 , -61.48664 , -55.853584 , -51.593952 ,

-43.21999 ], dtype=float32)

Coordinates:

* level (level) float32 1e+03 925.0 850.0 700.0 ... 50.0 30.0 20.0 10.0What do you think about this model – data comparison?

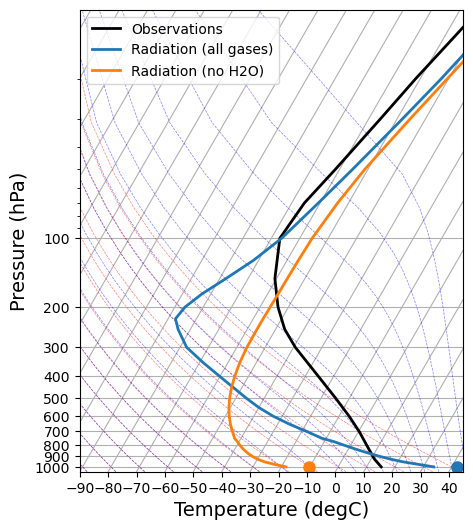

5. Effects of different gases on the radiative equilibrium profile#

Models are for experimenting and playing with!

We have just built a single-column radiation model with several different absorbing gases. We can learn about their effects by taking them away.

Radiative equilibrium without water vapor#

# Make an exact clone of our existing model

radmodel_noH2O = climlab.process_like(radmodel)

radmodel_noH2O.name = 'Radiation (no H2O)'

print(radmodel_noH2O)

climlab Process of type <class 'climlab.radiation.rrtm.rrtmg.RRTMG'>.

State variables and domain shapes:

Ts: (1,)

Tatm: (37,)

The subprocess tree:

Radiation (no H2O): <class 'climlab.radiation.rrtm.rrtmg.RRTMG'>

SW: <class 'climlab.radiation.rrtm.rrtmg_sw.RRTMG_SW'>

LW: <class 'climlab.radiation.rrtm.rrtmg_lw.RRTMG_LW'>

# Here is the water vapor profile we started with

radmodel_noH2O.specific_humidity

masked_array(data=[3.89581964e-06, 3.54524763e-06, 3.54524763e-06,

3.19467562e-06, 3.19467562e-06, 3.19467562e-06,

2.84410362e-06, 2.84410362e-06, 2.84410362e-06,

2.84410362e-06, 3.19467562e-06, 4.24639165e-06,

7.40153972e-06, 1.47635519e-05, 2.87864322e-05,

5.15736127e-05, 8.41768095e-05, 1.82336972e-04,

3.34835795e-04, 5.48334148e-04, 8.32297475e-04,

1.20530609e-03, 1.66420485e-03, 2.16517225e-03,

2.73274833e-03, 3.40374315e-03, 4.19708761e-03,

4.65107836e-03, 5.14468375e-03, 5.70349553e-03,

6.35135260e-03, 7.02690486e-03, 7.67826765e-03,

8.34470503e-03, 9.04199276e-03, 9.51912126e-03,

9.76417109e-03],

mask=False,

fill_value=1e+20)

Now get rid of the water entirely!

radmodel_noH2O.specific_humidity *= 0.

radmodel_noH2O.specific_humidity

masked_array(data=[0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.,

0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

mask=False,

fill_value=1e+20)

And run this new model forward to equilibrium:

# it's useful to take a single step first before starting the while loop

# because the diagnostics won't get updated

# (and thus show the effects of removing water vapor)

# until we take a step forward

radmodel_noH2O.step_forward()

while np.abs(radmodel_noH2O.ASR - radmodel_noH2O.OLR) > 0.01:

radmodel_noH2O.step_forward()

radmodel_noH2O.ASR - radmodel_noH2O.OLR

Field([-0.0099871])

skew = make_skewT()

for model in [radmodel, radmodel_noH2O]:

add_profile(skew, model)

What do you think you can learn from this about the radiative role of water vapor?

Exercise: radiative equilibrium without ozone#

Following the steps above, make another model, but this time instead of removing the water vapor, remove the ozone!

Make another skew-T plot comparing all three model results.

If you have time, try a third case in which you remove both the water vapor and the ozone!

6. Summary of radiative equilibrium results#

We used the

RRTMGradiation model with prescribed profiles of absorbing gases to calculate pure radiative equilibrium temperature profiles.Radiative Equilibriu means the temperatures that the surface and air column would have if radiation was the only physical process that could transfer energy between levels.

We computed several different radiative equilibrium profiles, with and without key absorbing gases

The profile without water vapor is much colder at surface and lower troposphere, but about the same in the stratosphere

The profile without ozone is much colder in the stratosphere, but about the same near the surface.

In fact there really isn’t a stratosphere at all without ozone! The temperature is nearly isothermal in the upper atmosphere in that profile.

However the really key takeaway message is that none of these radiative equilibrium profiles look much like the observations in the troposphere.

This strongly suggests that other physical processes (aside from radiation) are important in determining the observed temperature profile.

Plotting on the skew-T diagram makes it clear that all the radiative equilibrium profiles are statically unstable near the surface.

The next step is therefore to look at the effects of convective mixing on the temperatures of the surface and lower troposphere.

Credits#

This notebook is part of The Climate Laboratory, an open-source textbook developed and maintained by Brian E. J. Rose, University at Albany.

It is licensed for free and open consumption under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

Development of these notes and the climlab software is partially supported by the National Science Foundation under award AGS-1455071 to Brian Rose. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed here are mine and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

radmodel_co2 = climlab.process_like(radmodel)

print(radmodel_co2)

print(radmodel_co2.absorber_vmr)

radmodel_co2.absorber_vmr['CO2']=0.000410